-

Welcome

Welcome to the Lewin/Westgate/Quimby blog. This is where I am sharing some of my research on our ancestors. For me, genealogy started as an unsatisfactory list of names and dates, exactly what used to put me to sleep in history classes. But now that I know, for example, that my ancestor Littlefield Nash, who could not read, was a skilled scout in the woods around Lake George during the French and Indian War, that history has come alive for me. I hope it will for you, too.

My work over the years has been guided by two goals: to fit our people into their historical contexts, and to fill in the life stories of the women in our lines as best I could. Of course, the thrill of discovering an unknown fact was always the best treat, like when I found out that forebear Elizabeth Osgood Quinby was sentenced to be “whipped thirty stripes for fornication” by Salisbury Court in 1654. That sort of discovery spiced up the time spent under the shadow of the Jesus statue in my local LDS Family History Center.

For the foreseeable future, I plan to zoom in on the upper Connecticut River Valley, where many of the five generations before Marguerite Lewin and Arthur Westgate Quimby lived for over 200 years, starting with the earliest ancestral settlers. Dan Hertzler has kindly let me use one of his photos of Mt. Ascutney, which looms over the area, in one of its many guises.

I welcome questions, comments and corrections – if you prefer, you can send them to me at gayauerbach@hotmail.com. With best wishes to all, Gay

-

Dusty relics

Sometimes it’s the smallest artifact that raises the dust of a long-departed ancestor (or three).

This year, I spent a few days under the yellowing leaves and drenching rains of late September in a New Hampshire attic, rummaging through a trunk labeled “Westgate/Quimby.” The attic contained everything from the skirt of my great-grandmother’s wedding dress to the pictures of my grandparents’ travels in Germany in 1936. There were several hanks of mouse-brown hair, tied in ribbons.

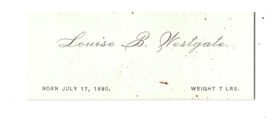

Least among the relics was a tiny envelope containing several itsy bitsy tintypes and a birth announcement. The card was about an inch high and two inches long and listed the birth of someone I had not heard of.

Ah ha – a mystery to solve… who was Louise B. Westgate, born in 1890 at 7 pounds, and why was her birth announcement in the trunk?

You can guess right away that Louise was somehow connected to William Westgate, my great great grandfather, known in the upper Connecticut River valley for his fine farm and handsome face. Many of his descendants have one of the 6-inch busts of him in plaster or, if they are lucky, bronze, fashioned by one of the artists of the Cornish Colony, I suppose. There are also a number of etchings of William Westgate showing him in profile, as he looked while reading outdoors in his rocking chair on a hot summer afternoon.[1]

With a bit of research, I found out that Louise B. was the daughter of William’s cousin Tyler Westgate. Although our William aspired to the genteel life, he didn’t have the education to be a probate judge like his cousin Tyler, and probably preferred breeding cattle anyway.[2] Cousin Tyler lived in Haverhill, New Hampshire, a town nestled about 50 miles farther up the Connecticut in a fertile oxbow of the river, where he was a postmaster, probate judge, entrepreneur, Mason and Republican. He had two wives, but after both had died, including the mother (Louise Bean) of baby Louise, he moved in with his sister Jennie Westgate in 1894, bringing his two little daughters with him. Baby Louise was just two years old when her mother died. (Jennie is also our William’s first cousin, of course.)

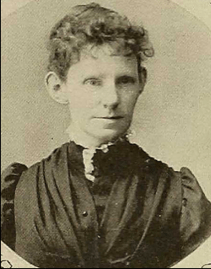

Jennie Westgate captured my interest right away. She is listed as head of the Westgate household in Haverhill in the 1900 and 1910 Censuses, and apparently housed at least two of her brothers, Tyler and George. Jennie never married, and served as mother to baby Louise and her older sister. She is typical of the many single women in our family who took on outsized responsibilities for their relatives.

Jennie Westgate, William’s first cousin (Find-a-Grave)Here is what The History of Haverhill has to say about Jennie (1848-1917):

“She was left with the care of the children of her brother, Tyler, and became first and foremost the lady of the house. She became interested in local history, and has been to the compiler of these pages a veritable help in furnishing notes and manuscripts. [A family historian!] She was a member of the Eastern Star [a charitable and religiously oriented club for wives and daughters of Masons]; her latest work was in connection with organizing the Haverhill chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution [Rachel, note]. She was the first regent [of her local DAR]. She was a member of the Congregationalist Church.”

Jennie made sure that Louise was educated, at Haverhill Academy (a school like K.U.A. in Meriden), and then at the Bradford Academy for Young Ladies in Bradford, Massachusetts. Louise and her sister “received their musical education from private teachers in Boston, Mass. They are members of the Eastern Star, and are both members of the Daughters of the American Revolution.”[3]

Louise met her future husband Edward A. Janes when he was a teacher boarding with her Aunt Jennie in Haverhill. The Janes moved around New England as a result of his career in education, eventually settling in Woodsville, N.H. where Edward was a superintendent of schools. Louise had three daughters and a son. Her daughter Virginia was born with “mental deficiency” and epilepsy.

Louise died quite young, in November 1937 at age 47.[4] Her obituary says that she was “a charming singer,” that she worked in the Congregational and Universalist churches and that she did many good works. She also took care of her impaired child at home until her death; Virginia was placed in Laconia State School after her mother died.[5]

SO, if you ever meet a Janes, say howdy. In the meantime…. who in the world are the people pictured in the tiny tintypes in the envelope with Louise’s birth announcement???

[1] I would love to be able to decipher the penciled signature of the artist who made the etchings. It looks like “Hamilton,” preceded by an initial that I can’t read.

[2] Biographical details about Tyler Westgate are from the History of the Town of Haverhill, New Hampshire by William F. Whitcher (1919), p. 670. Tyler was educated at Haverhill and Kimball Union Academies, and benefited from the fact that his father Nathaniel was a member of the bar and a judge of probate in Haverhill before him. Tyler himself was not a lawyer, which wasn’t a prerequisite for serving as a probate judge.

[3] History of Haverhill, p. 671.

[4] Louise was sent to New England Baptist Hospital for treatment for hypertension and kidney failure. See her Certificate of Death, Boston, Massachusetts, No. 9927, and the Groton Times (Groton, Vermont), November 12, 1937, p.1.

[5] Virginia was 10 when she went to Laconia and spent 17 years there before dying there in 1955, when I was four.

-

Set in Stone, Part Two

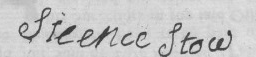

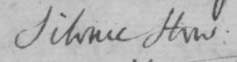

Silence Stow’s signature as it appears on the probate record naming her administrator of her first husband’s estate We left Silence (Hunt) mourning her husband Thomas Stow Jr. of Grafton, Massachusetts, who died in the beginning of January in 1750, after only a year and half of married life. The couple’s first child, Ruth, was less than a month old when her father was carried off, and Silence only 22.[1] She turned up at probate court in July, when she was made administrator of her husband’s estate; it was worth far less than that of his father, who had died four years earlier, and amounted to a lot less than he had inherited from his father.[2]

Like her mother, Silence found herself widowed with a suckling child at home. It’s no surprise, then, that on 16 May 1751 Reverend Aaron Hutchinson of Grafton recorded the intention of Silence Stow and Samuel Chase Junior of Sutton to marry, just a bit over a year after Thomas’ death.[3] This is when Silence née Hunt, once Stow, became Silence Chase, the woman whose dust lies under a slate stone in Trinity Cemetery in Cornish.

We can imagine for Silence a frugal life of hard work lived in a simple frame house in the land once occupied by the Nipmucks, where she spent the next 12 years producing seven children, starting with Samuel 6 in May of 1752. (Her seventh child Sarah is my direct ancestor; she was born in 1766.)[4] Her new husband took but a modest part in town affairs, appearing as an appraiser of James Whipple’s estate in 1760 and putting in a day or two of work on town roads from time to time. He is not among the soldiers from Grafton who served in the French and Indian War.[5]

During the years Samuel and Silence spent in Grafton the most vivid cultural trend must have been religious turmoil. Starting in the 1730s a wave of ecstatic, religious populism (known as the Great Awakening) rocked the conservative, authoritarian ministers of Sutton, Grafton, Worcester, Northhampton and other towns in the area (who often preached in each other’s churches; Jonathan Edwards himself showed up in the pulpit in Sutton at least once.)

In Sutton, where Samuel had grown up, Reverend David Hall grew to disparage the revivalist mood, and then to struggle hard against the so-called Separatists of his congregation, led by Ezekiel Cole, a converted Indian from Grafton. During the years just before Samuel 5’s marriage to Silence, “Hall filled his diary with reports of the ‘ruff Treatment’ and ‘sore abuse’ that he received….He was appalled by the wild Delusions that he witnessed during their tumultuous worship exercises. The noisy meetings featured peculiar sermons that, according to Hall, perverted the true meaning of the scriptures. Women preached and exhorted in public, while other separatists prophesied future events and recounted their visionary conversion experiences.”[6]

Meanwhile, the minister of Grafton, Aaron Hutchinson, the man who had married Silence and Samuel Chase, was a deeply unsympathetic man, also opposed to the more liberal, populist trends. He delivered one particularly chilling sermon at Newburyport on the subject of original sin, saying that children are “sinners, guilty and polluted,” liable to damnation and eternal misery. It’s no wonder that Silence (who “owned the Covenant” – that is, subscribed to the theology and rules of Hutchinson’s congregation) made sure that the minister baptized each of their seven children (to forestall that eternal misery) but took no other part in church controversies.

Her husband Samuel Chase 5 was relatively inconspicuous in Grafton and also within the Chase family. His father Samuel 4 Chase (1707-1800), on the other hand, was very well-known in his neighboring town of Sutton: energetic, healthy (he outlived his son Samuel by 10 years, dying at 93) and deeply involved in civic affairs as a justice of the peace and probate judge. The History of the Town of Sutton calls Samuel 4 Chase “one of the most enterprising inhabitants of the Town.” He “owned one-half of a saw-mill, dam, privilege of ye water, etc., and was principal shareholder of an iron refinery.”[7] It was this dynamo who roused most of his family to pull up stakes after the end of the French and Indian War in 1763 in order to try their fortunes in “the flourishing town of Cornish on the Connecticut River.”

Within a few years of arriving in Cornish, the Chases outnumbered all other residents in the town.[8] One of the least among them was our Samuel 5, who practiced the trade of blacksmith in Cornish beginning in 1764. (He had probably learned his trade from in the iron foundry that his father had financed back in Sutton.[9] ) Again in Cornish, Samuel’s father overshadowed him as a leader and man of ideas, I think, although Samuel Jr., as he was called in Cornish, did serve as selectman for one term in 1772. Meanwhile, Silence owned the Covenant in the Cornish Church in 1777; her son Samuel 6 and several daughters also joined. (It does not look to me as though her husband Samuel Chase, Jr. did so, which is interesting.)

When blacksmith Samuel 5 Chase died intestate in 1790, at age 61, a group of relatives took up the task of appraising and administering his estate. It included a few books, ironware, pewter, crockery, chairs, a table, clothing, a spinning wheel, a bed and linens, 60 pounds of “notes,” and 150 pounds of “wilde lands,” for a total of 233 pounds and 6 shillings. Note that about one quarter of Samuel’s assets were in debts due to him. Also note that he was not farming the “wild lands” that had undoubtedly been given him by his father.[10]

Silence herself slipped away a week short of her 67th birthday, in 1794. Somewhat unusually for a woman, she wrote a will a few months before she died, which wasn’t fully settled until 1800. She made a point of willing and bequeathing to her beloved son Samuel Chase “the desk that was formerly the property of his late Father,” along with one third of his father’s clothing, which was typical. Her son Joshua got a bed, a large kettle, a case of bottles, and one third of his father’s clothes; the heirs of her “late beloved son Peter Chase” each received three pounds and the last third of his father’s clothes. She gave all her household goods to her four married daughters to divide up evenly.

I hope one of my relatives gets to put a flower on the modest Silence’s grave one of these days.

[1] Baby Ruth was born 12 December 1749; Thomas died 8 Jan 1750 [MA VR, Grafton].

[2] Thomas Stow Senior’s estate was valued at £2,500 ; his son’s at £167. See Worcester Probate Files, Cases 57110 and 57111, available on American Ancestors.

[3] The marriage went forward on 29 May 1751. One reason it is so difficult to trace female ancestors is that widows almost always found new husbands. For example, Silence’s mother Martha married James Jackson of Leicester in December 1730; Jackson became guardian of Silence and her sisters Martha and Mary until Martha died in 1742. The only record of Martha Hunt Jackson’s death that I could find was a small reference in James Jackson’s report to the Probate Court (Middlesex Probate Files, Case 12297) that says “Martha, now deceased,” made in 1742. As a result, 14-year-old Silence then came into the guardianship of Jacob Whipple of Grafton, where many of her family’s connections from Concord and Sudbury then lived.

[4] MA VR, Grafton. The fact that the couple named their second child Ruth when she was born in 1754 suggests that the first Ruth, daughter of Thomas Stow, had died.

[5] See History of Grafton, Worcester County, Massachusetts by Frederick Clifton Pierce (1879), pp. 94-102.

[6] Winiarski, Douglas L., “New Perspectives on the Northampton Communion Controversy 1: David Hall’s Diary & Letter to Edward Billing,” Jonathan Edwards Studies 3, no. 2 (2013), p. 284.

[7] Benedict, Rev. William and Rev. Hiram Tracy, History of the Town of Sutton Massachusetts (1878), p. 622.

[8] “The children of these families of Chases were generally quite numerous; so those named Chase in town, for years, exceeded that of any other, or all other names combined.” Child, William H., Town of Cornish, New Hampshire with Genealogical Record, 1763-1910, Volume 1, p. 17.

[9] The Historical Society of New Hampshire has the account book of Samuel 5 Chase, blacksmith of Cornish.

[10] I infer this from the fact that Samuel Chase 4 wrote his own will four years after his son died, and but a few months before Silence died. In it he left only one pound to each heir of his deceased son Samuel, not even bothering to name Silence, his daughter-in-law, or her children. Most of Samuel’s other, living children got £150 in their father’s will, which was written six years before his death. I would guess that Samuel had already given his oldest son the equivalent in land, which was indeed valued at £150 in 1790.

-

Set in Stone: Part One

I’ve played Spelling Bee, I’ve played Wordle. But nothing is as much fun as the problem-solving involved in unraveling the mysteries of genealogy.

Take the intriguing grave marker of Silence Chase: it’s one of those slate slabs featuring an angel’s head and letters carefully carved in Times New Roman. It stands in Trinity Cemetery in what Find-a-Grave calls “Cornish City” next to the gravestone of her husband Samuel Chase (5).

Silence Chase’s gravestone in Trinity Cemetery, Cornish, NH Silence was one of the names that grabbed the grandchildren’s attention as we looked for interesting things in our grandparents’ house in Plainfield, N.H. in the Sixties. If you stood on the red leather couch in the sitting room you could see her name on the family tree, where she was listed as Silence Stone. Even better! My cousin recently reminded me of the fascinating name, so I delved into finding out who she was and where she came from.[1]

From original handwritten records, it quickly became clear that the family tree had the surname wrong, although no one can blame Aunt Carol for seeing Stone. Both handwriting and spelling were variable in the 18th century: here is one example of how Silence’s name was rendered:

How? Slow? Stone?

Actually, our ancestor’s last name was Stow, at least when that scribe wrote it. Child’s History of Cornish, New Hampshire, says as much. Child even records that our ancestor was born in Grafton, Massachusetts, but what he doesn’t say is that Silence was born with a different last name in another town, which always presents a genealogical challenge.[2]

Silence’s story starts with a death, which is where many stories started in the 1700s in New England. Her father, Thomas Hunt, expired in his hometown of Sudbury, Massachusetts in September of 1727, two months before our Silence was born.[3] The name his widow Martha chose for her “posthumous daughter” is a so-called virtue name, meaning that it celebrates a quality that Puritans prized, like Thankful, Patience and Wealthy. I’d like to think that widow Martha Hunt was mourning the fact that her husband Thomas had died an untimely death, leaving a silence in the family. This is completely unsubstantiated and magical thinking, I’m afraid. (My cursory survey found a few hundred other daughters called Silence in Massachusetts during the 18th century.)

In any case, widow Martha, mother of three girls, put her children into the guardianship of James Jackson of Sudbury in December of 1728, the man she subsequently married in 1730 as her second husband.[4] A few years later Jackson later submitted a record of the expenses he had incurred during the childhoods of Mary, Silence and Ruth Hunt, which is how we know that Silence had measles when she was a girl. Here is what he wrote in 1742 when he petitioned the Middlesex Court for reimbursement from the Hunt estate:

“Item: [Silence’s] support and maintenance from December the 20th 1728 till of the age of seven years, being five years £91

Expenses for medicine and attendance when she had the meazles [sic] and at other times £1- 10s-6pence”

Jackson requested £183 in total for serving as guardian of Martha’s three daughters, all of whom apparently went to other situations when they reached the age of seven. Sadly, the oldest daughter, Martha, died while in his care. James petitioned the estate for a refund of the money he spent on “mourning weeds [clothes] for guardian [i.e., himself]” and 10 pairs of gloves, which were traditionally given out during funeral processions.[5]

In 1741 Jacob Whipple of Grafton became guardian of Silence. She was now 14 years old (and he was an eminently respectable son of a deacon in that town).[6] The change of guardians occurred, you can learn by reading the probate record very carefully, because Martha, Silence’s mother, had died. This is probably when Silence removed to the newly created town of Grafton (incorporated in 1735), formerly known as Hassanamesit. In 1727, the year of Silence’s birth, 40 Englishmen had struck a deal with 7 Nipmuck Indians, the white men paying what seems a reasonable price for once of £2,500 for 7,500 acres.[7] (The tiny band of Nipmucks were so-called “praying Indians,” meaning they had been converted to Christianity, in their case by the proselytizer John Eliot) and therefore were treated with greater largesse than other natives.)

It was in Grafton that Silence became acquainted with Thomas Stow Jr., son of Thomas and Anna Stow, who was a year younger than she was. He was the son of Thomas Stow, Sr., a man with a tract of land in Grafton appraised at £1,656 in 1746 (with a widow and six sons to share the estate, although in this case his oldest son, Thomas, would receive the largest share, £879).[8] Her marriage to the young Thomas in 1748 was a good match for Silence, although sadly it would not survive for long… only long enough for one baby daughter to be born, in late 1749.

(To be continued as Set in Stone, Part Two)

[1] Silence was Mattie Quimby’s great, great, great, great grandmother. Silence’s daughter Sarah E. Chase married Abel Johnson; their daughter Martha married Daniel Cole; their daughter Sarah Cole married Earle Westgate; their son William Westgate married Charlotte Bryant; their daughter Martha (Grammy Great) married Elwin Quimby and so on.

[2] Child, William Henry, History of the town of Cornish New Hampshire, with genealogical records, 1763-1910, Volume II, (1911), p. 60.

[3] There was another Silence Stow born posthumously, to Mary (Wesson) and John Stow of Concord, Massachusetts in 1724. For a while I went on a wild goose chase tracking her down, until I realized that the Silence Stow of Grafton, born in 1727, was a better match. It took me a while to figure out that the maiden name of “our” Silence Stow was Hunt, not Stow and that she had a brief first marriage before marrying Samuel Chase 5. Full disclosure: when I checked Silence Chase’s bio on Find-a-Grave, the author called her Silence Hunt, which did not match William H. Child’s record. That was the hint I needed to eventually find her father Thomas Hunt of Sudbury. One of the difficulties of her case was the fact that the large families of Concord in Massachusetts Bay started migrating in droves once the French and Indian War ended, westward to Sutton and Grafton. The records of Concord/, Sudbury, and Sutton/Grafton are in two different counties, Middlesex and Worcester; the Stows’ land straddled Sutton and Grafton.

[4] MA VR, Sudbury. “Martha [Hunt] married James Jakson 4 Dec 1730.”

[5] Middlesex County Probate Files, Case 12297, available on American Ancestors (NEHGS).

[6]Ibid.

[7] My knowledge of Grafton’s history comes from Frederick Clifton Pierce’s book History of Grafton, Worcester County… (1879).

[8] Worcester County Probate Files, Case 57111, available on American Ancestors (NEHGS).

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.