We left Silence (Hunt) mourning her husband Thomas Stow Jr. of Grafton, Massachusetts, who died in the beginning of January in 1750, after only a year and half of married life. The couple’s first child, Ruth, was less than a month old when her father was carried off, and Silence only 22.[1] She turned up at probate court in July, when she was made administrator of her husband’s estate; it was worth far less than that of his father, who had died four years earlier, and amounted to a lot less than he had inherited from his father.[2]

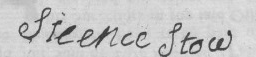

Like her mother, Silence found herself widowed with a suckling child at home. It’s no surprise, then, that on 16 May 1751 Reverend Aaron Hutchinson of Grafton recorded the intention of Silence Stow and Samuel Chase Junior of Sutton to marry, just a bit over a year after Thomas’ death.[3] This is when Silence née Hunt, once Stow, became Silence Chase, the woman whose dust lies under a slate stone in Trinity Cemetery in Cornish.

We can imagine for Silence a frugal life of hard work lived in a simple frame house in the land once occupied by the Nipmucks, where she spent the next 12 years producing seven children, starting with Samuel 6 in May of 1752. (Her seventh child Sarah is my direct ancestor; she was born in 1766.)[4] Her new husband took but a modest part in town affairs, appearing as an appraiser of James Whipple’s estate in 1760 and putting in a day or two of work on town roads from time to time. He is not among the soldiers from Grafton who served in the French and Indian War.[5]

During the years Samuel and Silence spent in Grafton the most vivid cultural trend must have been religious turmoil. Starting in the 1730s a wave of ecstatic, religious populism (known as the Great Awakening) rocked the conservative, authoritarian ministers of Sutton, Grafton, Worcester, Northhampton and other towns in the area (who often preached in each other’s churches; Jonathan Edwards himself showed up in the pulpit in Sutton at least once.)

In Sutton, where Samuel had grown up, Reverend David Hall grew to disparage the revivalist mood, and then to struggle hard against the so-called Separatists of his congregation, led by Ezekiel Cole, a converted Indian from Grafton. During the years just before Samuel 5’s marriage to Silence, “Hall filled his diary with reports of the ‘ruff Treatment’ and ‘sore abuse’ that he received….He was appalled by the wild Delusions that he witnessed during their tumultuous worship exercises. The noisy meetings featured peculiar sermons that, according to Hall, perverted the true meaning of the scriptures. Women preached and exhorted in public, while other separatists prophesied future events and recounted their visionary conversion experiences.”[6]

Meanwhile, the minister of Grafton, Aaron Hutchinson, the man who had married Silence and Samuel Chase, was a deeply unsympathetic man, also opposed to the more liberal, populist trends. He delivered one particularly chilling sermon at Newburyport on the subject of original sin, saying that children are “sinners, guilty and polluted,” liable to damnation and eternal misery. It’s no wonder that Silence (who “owned the Covenant” – that is, subscribed to the theology and rules of Hutchinson’s congregation) made sure that the minister baptized each of their seven children (to forestall that eternal misery) but took no other part in church controversies.

Her husband Samuel Chase 5 was relatively inconspicuous in Grafton and also within the Chase family. His father Samuel 4 Chase (1707-1800), on the other hand, was very well-known in his neighboring town of Sutton: energetic, healthy (he outlived his son Samuel by 10 years, dying at 93) and deeply involved in civic affairs as a justice of the peace and probate judge. The History of the Town of Sutton calls Samuel 4 Chase “one of the most enterprising inhabitants of the Town.” He “owned one-half of a saw-mill, dam, privilege of ye water, etc., and was principal shareholder of an iron refinery.”[7] It was this dynamo who roused most of his family to pull up stakes after the end of the French and Indian War in 1763 in order to try their fortunes in “the flourishing town of Cornish on the Connecticut River.”

Within a few years of arriving in Cornish, the Chases outnumbered all other residents in the town.[8] One of the least among them was our Samuel 5, who practiced the trade of blacksmith in Cornish beginning in 1764. (He had probably learned his trade from in the iron foundry that his father had financed back in Sutton.[9] ) Again in Cornish, Samuel’s father overshadowed him as a leader and man of ideas, I think, although Samuel Jr., as he was called in Cornish, did serve as selectman for one term in 1772. Meanwhile, Silence owned the Covenant in the Cornish Church in 1777; her son Samuel 6 and several daughters also joined. (It does not look to me as though her husband Samuel Chase, Jr. did so, which is interesting.)

When blacksmith Samuel 5 Chase died intestate in 1790, at age 61, a group of relatives took up the task of appraising and administering his estate. It included a few books, ironware, pewter, crockery, chairs, a table, clothing, a spinning wheel, a bed and linens, 60 pounds of “notes,” and 150 pounds of “wilde lands,” for a total of 233 pounds and 6 shillings. Note that about one quarter of Samuel’s assets were in debts due to him. Also note that he was not farming the “wild lands” that had undoubtedly been given him by his father.[10]

Silence herself slipped away a week short of her 67th birthday, in 1794. Somewhat unusually for a woman, she wrote a will a few months before she died, which wasn’t fully settled until 1800. She made a point of willing and bequeathing to her beloved son Samuel Chase “the desk that was formerly the property of his late Father,” along with one third of his father’s clothing, which was typical. Her son Joshua got a bed, a large kettle, a case of bottles, and one third of his father’s clothes; the heirs of her “late beloved son Peter Chase” each received three pounds and the last third of his father’s clothes. She gave all her household goods to her four married daughters to divide up evenly.

I hope one of my relatives gets to put a flower on the modest Silence’s grave one of these days.

[1] Baby Ruth was born 12 December 1749; Thomas died 8 Jan 1750 [MA VR, Grafton].

[2] Thomas Stow Senior’s estate was valued at £2,500 ; his son’s at £167. See Worcester Probate Files, Cases 57110 and 57111, available on American Ancestors.

[3] The marriage went forward on 29 May 1751. One reason it is so difficult to trace female ancestors is that widows almost always found new husbands. For example, Silence’s mother Martha married James Jackson of Leicester in December 1730; Jackson became guardian of Silence and her sisters Martha and Mary until Martha died in 1742. The only record of Martha Hunt Jackson’s death that I could find was a small reference in James Jackson’s report to the Probate Court (Middlesex Probate Files, Case 12297) that says “Martha, now deceased,” made in 1742. As a result, 14-year-old Silence then came into the guardianship of Jacob Whipple of Grafton, where many of her family’s connections from Concord and Sudbury then lived.

[4] MA VR, Grafton. The fact that the couple named their second child Ruth when she was born in 1754 suggests that the first Ruth, daughter of Thomas Stow, had died.

[5] See History of Grafton, Worcester County, Massachusetts by Frederick Clifton Pierce (1879), pp. 94-102.

[6] Winiarski, Douglas L., “New Perspectives on the Northampton Communion Controversy 1: David Hall’s Diary & Letter to Edward Billing,” Jonathan Edwards Studies 3, no. 2 (2013), p. 284.

[7] Benedict, Rev. William and Rev. Hiram Tracy, History of the Town of Sutton Massachusetts (1878), p. 622.

[8] “The children of these families of Chases were generally quite numerous; so those named Chase in town, for years, exceeded that of any other, or all other names combined.” Child, William H., Town of Cornish, New Hampshire with Genealogical Record, 1763-1910, Volume 1, p. 17.

[9] The Historical Society of New Hampshire has the account book of Samuel 5 Chase, blacksmith of Cornish.

[10] I infer this from the fact that Samuel Chase 4 wrote his own will four years after his son died, and but a few months before Silence died. In it he left only one pound to each heir of his deceased son Samuel, not even bothering to name Silence, his daughter-in-law, or her children. Most of Samuel’s other, living children got £150 in their father’s will, which was written six years before his death. I would guess that Samuel had already given his oldest son the equivalent in land, which was indeed valued at £150 in 1790.